Belva Lockwood Inn: The Woman Who Wouldn't Take "No" For An Answer

When Ike and Julie Lovelass bought the house at 249 Front Street in Owego, they had no idea who Belva Lockwood was. Now, it's her name that hangs on the sign in front of the inn.

"Actually, when we first toured the house, the gentleman who was showing us the house used Belva Lockwood as a selling point," says Julie, "She owned this property, she owned this property... We had no idea what he was even talking about."

Julie Lovelass didn't know who Belva Lockwood was, but now sports a #BeLikeBelva T-shirt.

Rewind to 2017 when the Lovelasses were looking for an old house to convert into an inn for their next business endeavor. You may remember hearing about that. The couple's search was featured on HGTV. Ike and Julie bought the home, which served as the meeting place of the Eagle's Club in the 1950s, and went to work restoring the house to how it looked when it was first built in 1872. That meant bringing back the front porch and the detailing along the gables and roof line that had been stripped off over the years in favor of a more modern look.

"When they took off all of the trim and things, they actually left a lot of it up in the attic," says Ike, "So we were able to take that and our carpenter was able to recreate things that were missing."

Ike Lovelass holding a picture of the "modernized" version of the house at 249 Front Street before it was restored to the Victorian style.

Before that house was ever built, a female seminary school sat on the property. That school was run by Belva Lockwood. When Belva came to Owego from the Buffalo area, she was 23 years old, a widow, and a single mother, and, as it turns out, she was a pretty big deal.

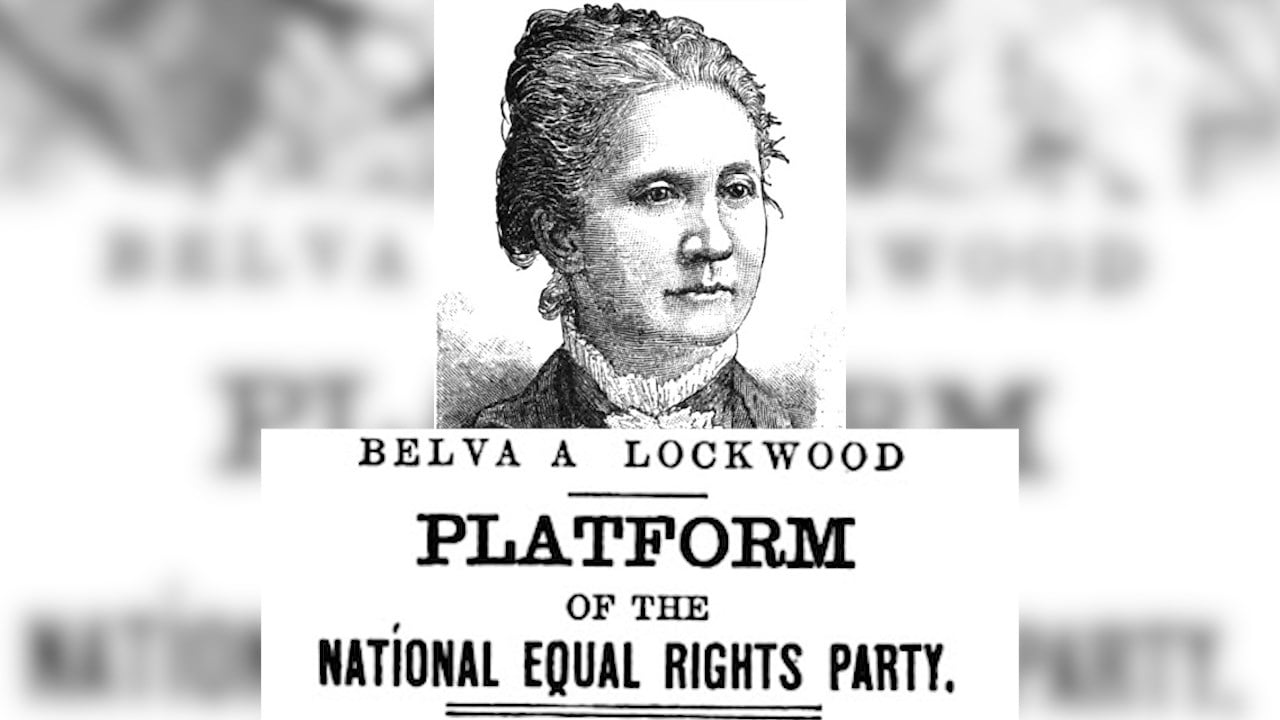

She was the first woman to officially run for president.

— Julie Lovelass, Co-Owner Belva Lockwood Inn

She ran twice. Once in 1884, then again in 1888. That was 36 years before women won the right to vote.

"One of her campaign slogans was 'I can't vote for me, but you can,'" says Ike.

Belva Lockwood was the first woman to run for President of the United States.

Lockwood ran on the Equal Rights Party line, a cause she had thrown herself behind at a young age.

"Her first real fight in the world was equal pay for all," says Julie.

That was when Belva got her first teaching job and realized her male colleagues were getting paid double what she was. She was 14 years old.

The fights got bigger from there. Setting her sights on a career in law, Lockwood sold the school and the Front Street property and moved to Washington D.C. She applied to Columbian School of Law and was rejected by the dean on the grounds that she "would prove a distraction to the young men." Instead, she would go to the National University School of Law where she was set to graduate with honors when yet another obstacle was thrown her way.

"They wouldn't give her the diploma," says Emma Sedore, Tioga County Historian, "Sure, you can come to our college, pay our fees, but we're not going to give you that piece of paper."

Incensed, Belva went above all of their heads. She wrote to the President of the United States, Ulysses Grant.

"A week later, boom," says Sedore, snapping her fingers, "They gave her that degree."

Next, it would be the Supreme Court that would try to say "no" to Belva. In 1876 Belva petitioned the Supreme Court to allow her to argue a case at the federal level. At the time, women were barred from doing so. They turned her down, but she continued to petition congress to write a law allowing female lawyers the same rights as their male counterparts.

It took years, but finally, on March 3, 1879, Congress passed the law that said "no person should be excluded from practicing as an attorney and counsellor at law from any court of the United States on account of sex" allowing women to argue cases in the Supreme Court. Belva was the first to do so.

My cause was the cause of thousands of women. I pushed forward when I could and retreated when I had to, but always returned to the attack.

— Belva Lockwood

"It just boggles your mind," says Ike, "What's crazy to me is how nobody knows about her."

This picture of Belva Lockwood hangs over the fireplace in the front room of the Belva Lockwood Inn.

While most haven't learned about her in school, Belva Lockwood's efforts haven't gone unnoticed. She received an honorary law degree from Syracuse University in 1909, her face was on a postage stamp, towns have been named after her, and her picture hangs in the National Portrait Gallery.

The house on Belva's old Owego property is now a 5-room inn.

After learning about her story, Ike and Julie have taken it upon themselves to spread the word. Books about Belva and the suffrage movement sit on the bedside tables in each room of the inn, encouraging guests to read more and draw inspiration from the woman who wouldn't take 'no' for an answer.

Be daring, courageous, true to your beliefs, and simply, #BeLikeBelva.